Across the

world, politically connected tycoons are feeling the squeeze - Economist

May 7th

2016 | From the print edition

·

TWO YEARS ago The Economist constructed an index of crony

capitalism. It was designed to test whether the world was experiencing a new

era of “robber barons”—a global re-run of America’s gilded age in the late 19th

century. Depressingly, the exercise suggested that since globalisation had

taken off in the 1990s, there had been a surge in billionaire wealth in

industries that often involve cosy relations with the government, such as

casinos, oil and construction. Over two decades, crony fortunes had leapt

relative to global GDP and as a share of total billionaire wealth.

It may seem that this new golden era of crony capitalism is coming to a

shabby end. In London Vijay Mallya, a ponytailed Indian tycoon, is fighting

deportation back to India as the authorities there rake over his collapsed

empire. Last year in São Paulo, executives at Odebrecht, Brazil’s largest

construction firm, were arrested and flown to a court in Curitiba, a southern

Brazilian city, that is investigating corrupt deals with Petrobras, the

state-controlled oil firm. The scandal, which involves politicians from several

parties, including the ruling Workers’ Party, is adding to pressure on Brazil’s

president, Dilma Rousseff, who is facing impeachment on unrelated charges.

A Malaysian investment fund, 1MDB, that is answerable to the prime

minister, is the subject of a global fraud probe. Supporters of Rodrigo

Duterte, the front-runner to win the presidential election in the Philippines

on May 9th, hope he will open up a feudal political system that has allowed

cronyism to flourish. In China bosses of private and state-owned firms are now

routinely interrogated as part of Xi Jinping’s purge of “tigers” (a purge that

has left Mr Xi’s family well alone). Worldwide, tycoons’ offshore financial

cartwheels have been revealed through the Panama papers.

The economic climate has been tough on cronies, too. Commodity prices

have tanked, cutting the value of mines, steel mills and oilfield concessions.

Emerging-market currencies and shares have fallen. Asia’s long property boom

has sputtered.

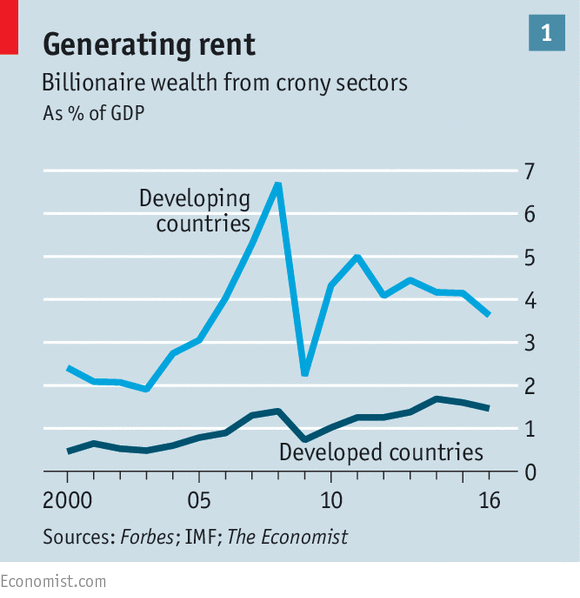

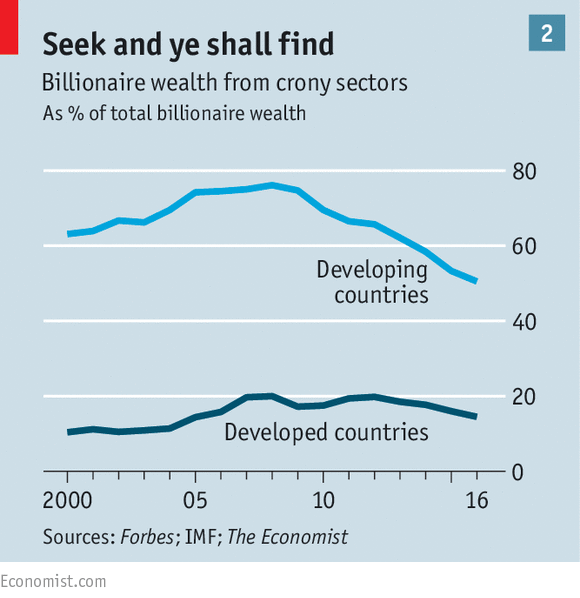

The result is that our newly updated index shows a steady shrinking of

crony billionaire wealth to $1.75 trillion, a fall of 16% since 2014. In rich

countries, crony wealth remains steadyish, at about 1.5% of GDP. In the

emerging world it has fallen to 4% of GDP, from a peak of 7% in 2008 (see chart

1). And the mix of wealth has been shifting away from crony industries and

towards cleaner sectors, such as consumer goods (see chart 2).

Despite this slowdown, it is too soon to say that the era of cronyism is

over—and not just because America could elect as president a billionaire whose

dealings in Atlantic City’s casinos and Manhattan’s property jungle earn him

the 104th spot on our individual crony ranking.

Behind the crony index is the idea that some industries are prone to

“rent seeking”. This is the term economists use when the owners of an input of

production—land, labour, machines, capital—extract more profit than they would

get in a competitive market. Cartels, monopolies and lobbying are common ways

to extract rents. Industries that are vulnerable often involve a lot of

interaction with the state, or are licensed by it: for example telecoms,

natural resources, real estate, construction and defence. (For a full list of

the industries we include, see article.)

Rent-seeking can involve corruption, but very often it is legal.

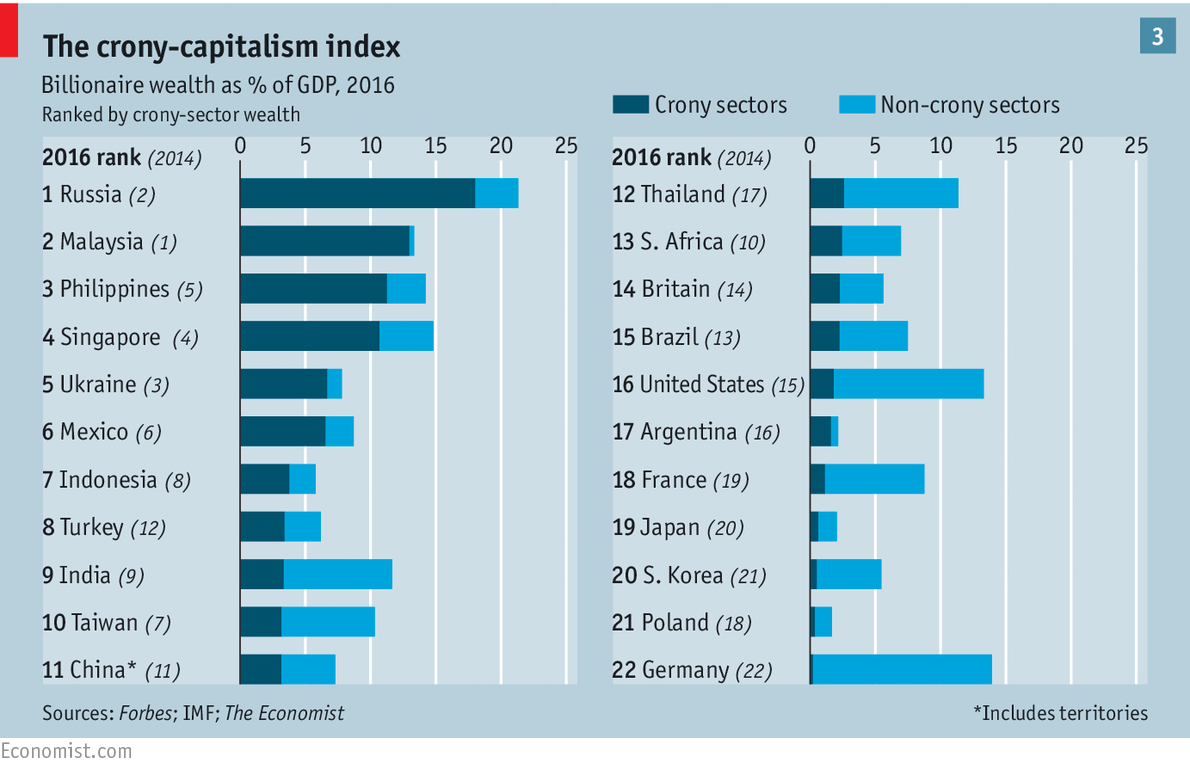

Our index builds on work by Ruchir Sharma of Morgan Stanley Investment

Management and Aditi Gandhi and Michael Walton of Delhi’s Centre for Policy

Research, among others. It uses data on billionaires’ fortunes from rankings by Forbes. We label each

billionaire as a crony or not, based on the industry in which he is most

active. We compare countries’ total crony wealth to their GDP. We show results

for 22 economies: the five largest rich ones, the ten biggest emerging ones for

which reliable data are available and a selection of other countries where

cronyism is a problem (see chart 3). The index does not attempt to capture

petty graft, for example bribes for expediting forms or avoiding traffic

penalties, which is endemic in many countries.

The rich world has lots of billionaires but fewer cronies. Only 14% of

billionaire wealth is from rent-heavy industries. Wall Street continues to be

controversial in America but its tycoons feature more prominently in populist

politicians’ stump speeches than in the billionaire rankings. We classify

deposit-taking banking as a crony industry because of its implicit state

guarantee, but if we lumped in hedge-fund billionaires and other financiers,

too, the share of American billionaire wealth from crony industries would rise

from 14% to 28%. George Soros, by far the richest man in the hedge-fund game,

is worth the same as Phil Knight, a relative unknown who sells Nike training

shoes. Mr Soros’s fortune is only a third as large as the technologyderived

fortune of Bill Gates.

Developing economies account for 43% of global GDP but 65% of crony

wealth. Of the big countries Russia still scores worst, reflecting its

corruption and dependence on natural resources. Both its crony wealth and GDP

have fallen in dollar terms in the past two years, reflecting the rouble’s

collapse. Their ratio is not much changed since 2014. Ukraine and Malaysia

continue to score badly on the index, too. In both cases cronyism has led to

political instability. Try to pay a backhander to an official in Singapore and

you are likely to get arrested. But the city state scores poorly because of its

role as an entrepot for racier neighbours, and its property and banking clans.

Encouragingly, India seems to be cleaning up its act. In 2008 crony wealth

reached 18% of GDP, putting it on a par with Russia. Today it stands at 3%, a

level similar to Australia. A slump in commodity prices has obliterated the

balance sheets of its Wild West mining tycoons. The government has got tough on

graft, and the central bank has prodded state-owned lenders to stop giving

sweetheart deals to moguls. The vast majority of its billionaire wealth is now

from open industries such as pharmaceuticals, cars and consumer goods. The

pin-ups of Indian capitalism are no longer the pampered scions of its business

dynasties, but the hungry founders of Flipkart, an e-commerce firm.

In absolute terms China (including Hong Kong) now has the biggest

concentration of crony wealth in the world, at $360 billion. President Xi’s

censorious attitude to gambling has hit Macau’s gambling tycoons hard. Li

Hejun, an energy mogul, has seen most of his wealth evaporate. But new

billionaires in rent-rich industries have risen from obscurity, including Wang

Jianlin, of Dalian Wanda, a real-estate firm, who claims he is richer than Li

Ka-shing, Hong Kong’s leading business figure.

Still, once its wealth is compared with its GDP, China (including Hong

Kong) comes only 11th on our ranking of countries. The Middle Kingdom

illustrates the two big flaws in our methodology. We only include people who

declare wealth of over a billion dollars. Plenty of poorer cronies exist and in

China, the wise crony keeps his head down. And our classification of industries

is inevitably crude. Dutch firms that interact with the state are probably

clean, whereas in mainland China, billionaires in every industry rely on the

party’s blessing. Were all billionaire wealth in China to be classified as

rent-seeking, it would take the 5th spot in the ranking.

The last tycoons

A possible explanation for the mild improvement in the index is that

cronyism was just a phase that the globalising world economy was going through.

In 2000-10 capital sloshed from country to country, pushing up the price of

assets, particularly property. China’s construction binge inflated commodity

prices. In the midst of a huge boom, political and legal institutions struggled

to cope. The result was that well-connected people gained favourable access to

telecoms spectrum, cheap loans and land.

Now the party is over. China’s epic industrialisation was a one-off and

global capital flows were partly the result of too-big-to-fail banks that have

since been tamed. Optimists can also point out that cronyism has stimulated a

counter-reaction from a growing middle class in the emerging world, from

Brazilians banging pots and pans in the street to protest against graft to

Indians electing Arvind Kejriwal, a maverick anti-corruption campaigner, to run

Delhi. These public movements echo America’s backlash a century ago. The Gilded

Age of the late 19th century gave way to the Progressive Era at the turn of the

20th century, when antitrust laws were passed.

Yet there is still good reason to worry about cronyism. Some countries,

such as Russia, are going backwards. If global growth ever picks up commodities

will recover, too—along with the rents that can be extracted from them. In

countries that are cleaning up their systems, or where popular pressure for a

clean-up is strong, such as Brazil, Mexico and India, reform is hard. Political

parties rely on illicit funding. Courts have huge backlogs that take years to

clear and state-run banks are stuck in time-warps. Across the emerging world

one response to lower growth is likely to be more privatisations, whether of

Saudi Arabia’s oil firm, Saudi Aramco, or India’s banks. In the 1990s botched

privatisations were a key source of crony wealth.

The final reason for vigilance is technology. In our index we assume

that the industry is relatively free of government involvement, and thus less

susceptible to rent-seeking. But that assumption is being tested. Alphabet, the

parent company of Google, has become one of the biggest lobbyists in Washington

and is in constant negotiations in Europe over anti-trust rules and tax. Uber

has regulatory tussles all over the world. Jack Ma, the boss of Alibaba, a

Chinese e-commerce giant, is protected by the state from foreign competition,

and now owes much of his wealth to his stake in Ant Financial, an affiliated

payments firm worth $60 billion, whose biggest outside investors are China’s

sovereign wealth and social security funds.

If technology were to be classified as a crony industry, rent-seeking

wealth would be higher and rising steadily in the Western world. Whether

technology evolves in this direction remains to be seen. But one thing is for

sure. Cronies, like capitalism itself, will adapt.

http://www.economist.com/news/international/21698239-across-world-politically-connected-tycoons-are-feeling-squeeze-party-winds?cid1=cust/ednew/n/bl/n/2016055n/owned/n/n/nwl/n/n/n/n